Note: I found this today while clearing out old zip files and it amused me. It’s odd reading stuff you yourself wrote nearly forty years ago. This comes from way back in the 80s, when I was the owner/director of a language school in Buenos Aires. It was originally published in the Buenos Aires Herald.

At the end of every year I have the unenviable task of cleaning and clearing out the Victoria School book room. This means having to decide what to bin and what stays in, effectively a trade off between the squirreling instinct and the pragmatics of shelf space.

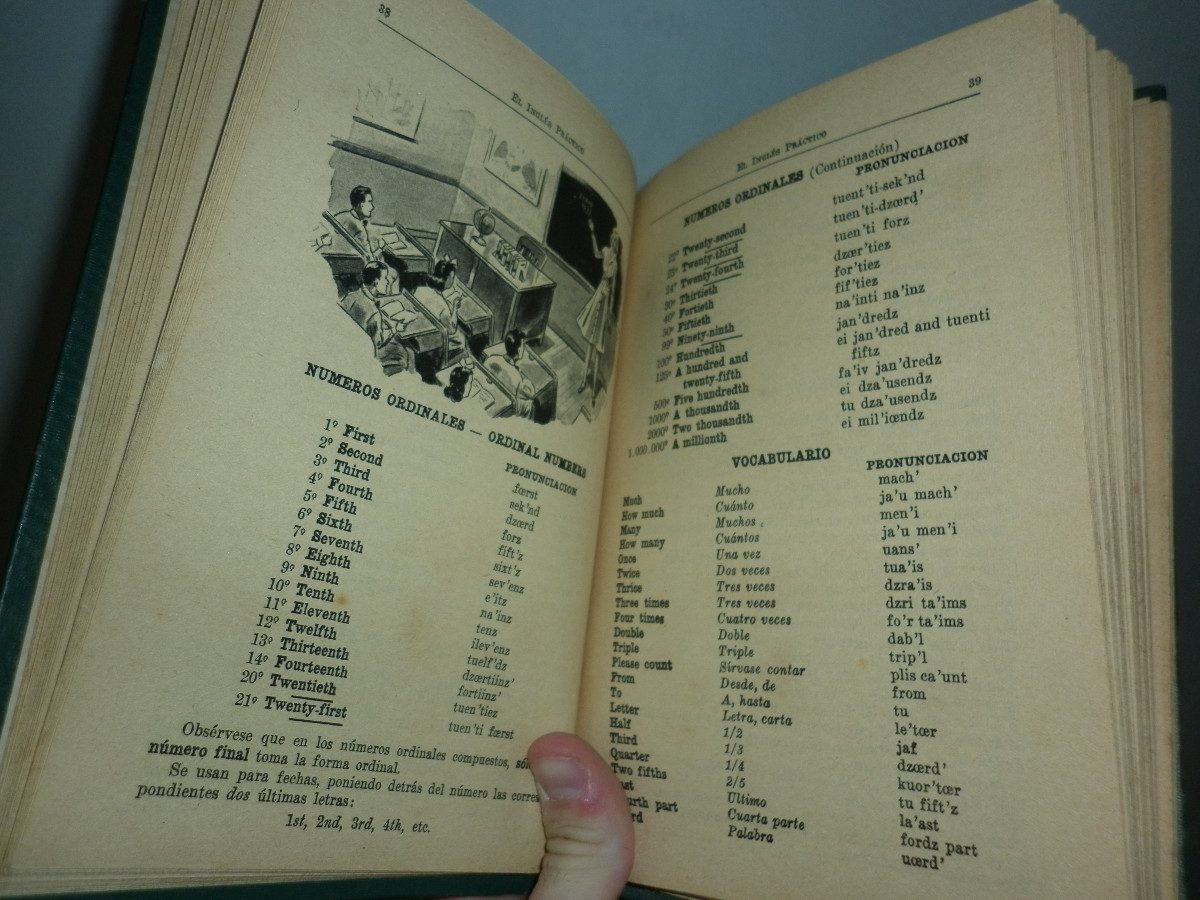

One book which seems to survive the chop every year is a rather tattered volume called El Inglés Práctico. No, not my long awaited autobiography (which could certainly never go out under that title, on account of how I am by all accounts un inglés bastante impráctico), no, this is a course book for learners of English from way back when. Look as I would, I could nowhere find a date of publication but judging by the wardrobe of the characters in the line drawings I would place it somewhere in the late twenties or early thirties.

I should perhaps make it clear that this is a wholly Argentine book, and the characters and situations are predominantly set in Argentina. The first vocabulary items presented in volume one are ‘the father’, ‘the mother’ and ‘the honest family’. In fact, honesty would seem to be the theme of this first unit. Consider some of the sentences in the first lectura y conversación:

The father is kind, the mother is good and the son is gentle. The family is good and honest. Is it good and honest ? Yes, it is. Robert is the child. He is very honest. The grandfather and the grandmother are very old and (yes, you’ve guessed it) they are honest.

I’m not making this up. Honest.

Another thing I liked was the pedagogical device of giving in each unit a short list of frases usuales en clase, basically a list of teacher-talk items useful for classroom management. In the list of these ‘useful phrases’ accompanying the very first unit, along with the expected ‘stand up’, ‘sit down’ and ‘exchange places’, appear enjoinders to ‘pronounce well’, and, presumably lest this not produce the desired results, to ‘pronounce better’. Would that things were so simple.

The second lesson introduces some rather more useful vocabulary, setting honesty aside for a while in order to concentrate on the wardrobe. A brief extract should give you the flavour:

Is this bodice flannel or woolen ? It is neither flannel nor woolen, but cotton. Have you not a pretty fan ? And has he not new braces ? No, I have a simple one and he has old ones.

Most teachers I know would be probably be happy if their students came up with these structures after two years, if at all, let alone two lessons, considering the inverted negative questions, anaphoric references, pronominalisation, etc., involved.

Leafing through to the end of the book I cannot resist sharing with you the visit to the peluquero de caballeros (all captions, instructions, etc., in the book are in Spanish, a trend, incidentally, which is returning now in much new ELT material). Consider the advice the customer (looking rather like Ramon in the illustrations of the famous Buenos Aires Herald publication Ramon Writes) is given:

Your hair is very dry and dull; you should put some brilliantine on it every day. I have some which is very good and makes the hair glossy without greasing it.

The customer (hereinafter to be referred to as Ramon and that’s without an accent, please, Mr. Typesetter*), agrees to the transaction at the confusing price of six dollars a bottle, at which the hairdresser somewhat alarmingly comments:

I shall give you a little friction, shall I not ?

Fortunately for sensitive readers, Ramon, after considerable thought (and no doubt working it out that if a bottle of brilliantine sets him back six bucks then a friction job is likely to leave him in the poor house) rejoins “No, it is not necessary’. After all, to sell El Inglés Práctico in schools they would have wanted to keep the ‘G’ rating.

Our students certainly come a long way by the end of the book. I quote from the final unit of what I must ask you to remember is a first year book:

Thus, from the hands of this prodigal son of the Independence, surged this sublime blue and white ensign, which today flies proudly and arrogantly from the masts of ships, public buildings and Argentine forts.

Unfortunately I don’t have a copy of El Inglés Práctico – Segundo Libro, but I should be very interested to see it. The ‘Argentine forts’ seem to have disappeared too.

I am at present teaching a group in the Victoria School who are hoping to sit for the University of Cambridge Proficiency Examination at the end of this year, at a level corresponding to some eight or nine years of language study. With respect to my students, many of them would be pushed to come up with something quite so elegant as the above eulogy to Belgrano. Those teachers of long ago certainly must have known something we don’t know today.

______________

* there were typesetters in those days – how times have changed.