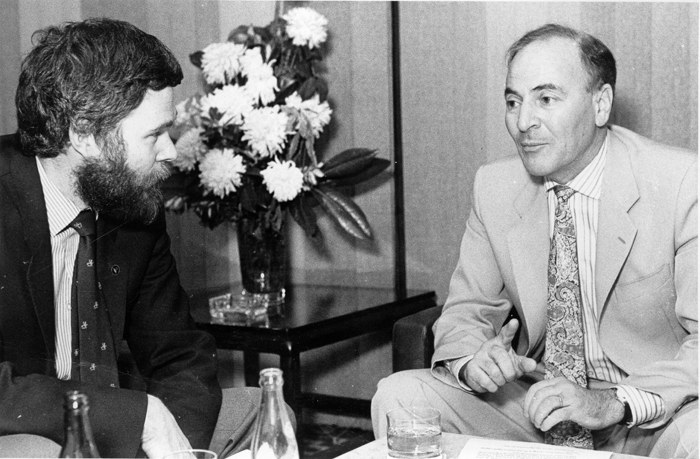

Interviewed by Martin Eayrs for the Buenos Aires Herald, 1998

Louis (L.G.) Alexander has recently been in Argentina on a lecture trip and the Herald spoke to him at his hotel.

Louis Alexander interviewed by Martin Eayrs for the Buenos Aires Herald, 1998. Photo Pilar Bustelo.

Louis Alexander recognises that he has been somewhat out of the public eye since he wrote his last book in 1979, but he’s now back on the road involved in what he calls “profile raising”, (nine countries so far this year). He fears that many people may have been wondering what happened to him; whether he has died, retired or just disappeared at the height of his career – the truth is that he’s been working on a new book, the ‘Longman English Grammar’, originally scheduled to take two years but in fact requiring seven, and he has only recently been “let out”.

He sees his new book as plugging a necessary gap, as there has been no new EFL (English as a Foreign language) grammar since 1960. It is aimed at anyone, teacher or student, native-speaker or otherwise, who needs an EFL reference grammar; our language has so far, he says, been abominably served in this respect. Having finally finished this he now sees his main priority as producing accompanying exercises for the grammar which will be “different to anything on the market”, and which will be based on inductive learning techniques that will require the reader to work out the rules for himself rather than being spoon fed with them. These new exercises will be “self-standing”, and thus not necessarily linked to the grammar, but will cross-reference back to it for the “whole story”.

He’s visited Rosario, Cordoba and Buenos Aires on his lecture tour this time round, and observes that the general level of ELT (English Language Teaching) remains as high as on his last visit here in 1972, and that the enormous enthusiasm for learning English continues unabated. A lot of very young people come to his lectures – mainly students who are going to be teachers – and it is from these, he says, that we can tell that the level and enthusiasm are still high. (He admits to a certain satisfaction at finding that many of these have learned from his books).

Outside his professional interests here, however, he finds that Argentina is suffering a “general lack of self confidence”, a “pervasive gloom”, which he did not notice on his previous visit, and this disturbs him.

Asked about his first textbooks (‘First Things First’, ‘Practice and Progress’, ‘Developing Skills’, etc.) and their continuing usefulness today, he stresses that the principal reason for changing textbooks is boredom, more from the point of view of the teacher than the student, but considers that old courses, if they were good in the first place, don’t “die” as much as “fade away”, and is pleased to point out that his first book, ‘Sixty Steps to Precis’ (1962), is still in print. In fact he was particularly gratified when told by a teacher in Rosario that she still hadn’t found a better system for teaching composition than that used in his earliest books, and for that reason she still used them.

He feels that textbooks in general carry the stamp of the individual who produces them, and that this personal quality cannot be replaced by “mere analysis” in books produced by committees. Course books are today becoming glossier, and this implies enormous investment on the parts of the author (seven years for his latest book) and the publisher, who may put “all their shirts” on a flagship course. For this reason, as well as the lack of research facilities and resources in general, local materials cannot usually compete with imported publications, having as they do that “homemade look”.

The EFL market has been dominated recently by British-produced materials, and he feels that this is because North America has been over-involved in the enormous problems caused by immigrant populations within its own boundaries. This he feels may well be changing and North American publishers are now beginning to look beyond their own shores. He does note however that in the past British publishers have been more prepared to make concessions as a means of establishing a foothold than their North American counterparts; (“in 1956 we were going into Egypt when everyone else was coming out”).

No, he does not consider that the market for EFL material is saturated. Perhaps this may be true in the case of Primary and Secondary course books, but he feels there are still “a dozen gaps” waiting to be filled, such as for example the Grammar he has just finished, or perhaps an updated approach to the teaching of composition to satisfy the teacher in Rosario.

Asked whether structured readers like those he has written offer an advantage over ungraded, “authentic” material, he points out that learners quickly become discouraged unless they can read with ease and confidence, and that his readers have been novels, which do not lend themselves so readily to reading for gist (general meaning). In any case, he considers that “authentic” materials culled from the fields of, say, advertising, immediately become unauthentic when incorporated into an EFL package, and that, unfortunately, many teachers insist on analysing every nuance of such texts, thus often invalidating an exercise which in essence consists of getting the general idea only.

He regrets the high cost of English Language teaching materials in this country, and as a teacher sympathises with students who resort to photocopying books or parts of books they simply cannot afford to buy. He is, however, “chagrined” as an author, deeply involved as he is in the right to copyright, and he takes the view that if we go on eroding copyright we erode creativity. People may be forced out of business, he continues, if what they create is copied, and he suggests that even token payment may be better than none, as long as the principle of copyright is observed. (He does however concede that he would prefer his books to be photocopied than another author’s).

He has nothing but contempt for those “teachers” who reject course books in favour of something chosen at random on the way into work. He considers that what these people are actually doing is to create a “totally unedited, unfiltered textbook, without the benefit of any thinking, planning, organisation”. This only occurs in his opinion with a certain class of native-speaker teacher who is “too clever by half”. He makes this point with warmth and evident conviction.

And his spirit continues to rise as he talks about teaching methodology (or methodologies). He himself approves of no teacher or method which preaches one methodology at the expense of others, disapproving strongly of what he refers to as “linguistic evangelism”. He values an approach which is “open-minded and catholic in its view, and which recognises the enormous variety of methods”. His voice rises in time with his temper as he remonstrates: “many of these linguistic evangelists have never exposed themselves to the fiery furnace of the classroom to see whether their marvellous ideas will stand up for five minutes”. A nerve has clearly been touched here.

One quickly gets the impression that he is a pragmatist – “no ideal method … we must look at circumstances and avoid blanket views … learning a language is very hard … different people have different ceilings, just as some people drive (cars) better than others”.

He applies the same practical point of view to the commercial aspects of his work – “Competition between publishers must be good”. A firm believer in market forces and the survival of the fittest, he sees it as not the fault of the publishers if the consumer is faced with a bewildering plethora of ELT material. It is up to the consumer to filter the material. In this respect he suggests the need for some independent consumer association, like the British Which magazine, which could provide an objective description and evaluation to the consumer; he finds that some very good material unfortunately has a very short “shelf life”.

He favours an international approach to English Language Teaching, considering that the cultural aspects are more suitable to specialised, advanced courses. The language that enables a Japanese tourist to converse with a shopkeeper in Buenos Aires should, he says, be divorced from any one culture, and he feels that in Argentina general English language teaching should on the one hand enable Argentines to communicate with visitors (regardless of where they are from), and on the other enable Argentines who may travel abroad to do the same. What he is very anxious to avoid is any charge of “linguistic imperialism” – we should at all times respect local methods and local learning traditions.

He was, finally, very patient with this interviewer, and he and his wife Julie were charming and most cooperative throughout a long interview in what has been a tight schedule.

His only complaint – he does wish that people here could try to be “a little more cheerful”.

=========================

The name of L.G. Alexander will be familiar to anyone who has been in any way connected with the teaching or learning of English during the last twenty-five years. Many readers of the Herald must have come into contact with one of his course books , which include ‘New Concept English’ (First ‘Things First’ , ‘Practice and Progress’, etc), ‘Look Listen and Learn’ , ‘Target’ , ‘Mainline’ , ‘Follow Me’, and most recently ‘Plain English’. His graded readers still continue to delight and his language practice books are used by literally millions of people all over the world.

Yet there is more to the man than just writing text books for classroom use. His expertise is based on lengthy teaching experience in Greece and Germany, after which he was included in the Council of Europe’s Modern Language Teaching Committee and he was in fact one of the authors of The Threshold Level and Waystage, publications which lay down guidelines for the coherent and consistent teaching of modern languages in Europe today and also provide the rationale for many modern “communicative” language courses. Currently he is adviser to the University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate for the Cambridge Certificate in English for International Communication.