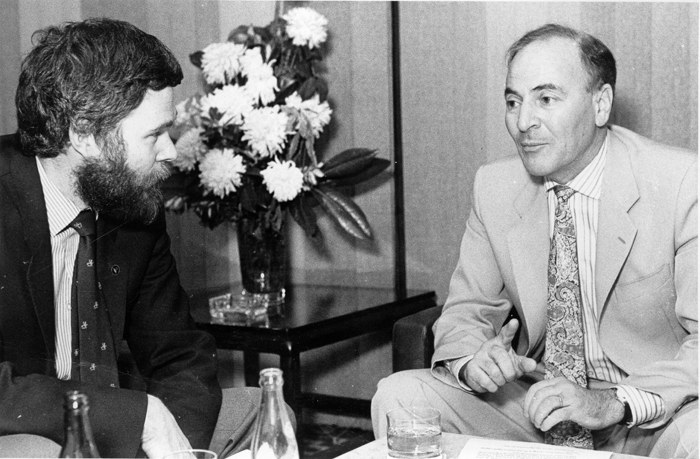

23 July 1991, by Martin Eayrs for the Buenos Aires Herald

Professor Sir Randolph Quirk was in Buenos Aires last week as part of the increasing activity surrounding the British Council’s reinitiation of activities in Argentina. The Herald spoke to him at his hotel.

ME Perhaps I can start by combining two questions. Have you been to Argentina before, and what is the purpose of your present visit?

RQ This is my first visit to Argentina and I’m extremely happy to be here. I am a member of the board of the British Council and I’ve been very keen to reopen in Argentina. We opened only in May of this year so I’m in on the ground floor, as it were. Another member of the board, the novelist Baroness James (better known perhaps as P. D. James) was here some weeks ago and I wanted to see the British Council activity for myself. I knew Harold Fish [Buenos Aires representative of the British Council – ME] in Germany and this morning I went over and had a look at the building. I’m well pleased with what the Council is doing here and I’m very impressed by the warmth that Argentina is showing to the British Council.

ME There are a great many ‘varieties’ of English in use in the world today, some of them differing considerably from the Standard English used in Britain and the United States. In some cases what passes for ‘English’ in some parts of the world is practically unintelligible to speakers of ‘English’ in others. Do you think this divergence might eventually lead to a splintering away, to the formation of separate languages?

RQ I think we are talking about two different kinds of language variation here. There is the variation between British, American, Australian and South African English, and these are really like dialectal variations within one language From that point of view the variation between one region or one nation’s English and another’s is no different from the relation between Iberian Spanish and other forms of Spanish in Mexico, Argentina, Chile, etc. Just as an Englishman can make a fair guess at identifying an Australian, a Scotsman, a Welshman or an American, some of us are a bit cleverer and can recognise not only an American but also a ‘New Englander’ or a ‘Southerner’. This is certainly true for Spanish too – in Spain a Spaniard can identify a Mexican or an Argentinian, for example, – those two stand out. But in addition to that kind of variation there is a fundamentally different kind of variation – exemplified by so called Indian English or Nigerian English, Bangla Desh English, etc. Although the use of English in India or Nigeria is different to the use of English in the Soviet Union or Germany it varies from native English for the same reason, because of the interference of whatever the mother language is. I regard these varieties as inherently unstable. You and I can usually tell if a foreigner speaking to us is a Swede, a Spaniard, etc. They’ve got not merely a foreign accent but a foreign accent we associate with a particular linguistic community. They’re inherently unstable because the better learned the language is, the more that accent disappears. So by a kind of irony the person who speaks Indian English most recognisably is the person who by common sense standards speaks it worst. And they’re inherently unstable from another more fundamental point of view. Most of the native varieties of English have not been institutionalised – only two have been, British and American English – but it would be perfectly possible to institutionalise Australian English and New Zealand English.

ME Why has this not happened?

RQ Why hasn’t Argentinian Spanish been institutionalised? When some people talk of ‘argentino’ in the same way as some people say ‘he’s speaking Australian’ this is not exactly a joke. Sometimes it’s a political assertion. In the media the differences between Iberian and Argentinian Spanish melt away except for some pronunciation features. Some lexical items have to be used because they describe cultural features that obtain here and not in the Iberian Peninsula. It’s interesting that although Argentina and Mexico have been established a very long time the folk wisdom – whether in government, in power in the church or the media or just the folk downstairs – there is, even if they don’t like to give it verbal expression, some kind of pride in speaking a world language. They don’t want to hive off. We are not stargazers and anything can happen. We know that a single language has in the past split up into different languages, but in the past the starting point was different. In the case of Romance languages developed from Latin, the countries of France, Romania, Portugal and Spain were not settled after the withdrawal of the Roman legions by a solid mass of standard Latin-speaking peoples. There were little bits and pieces of Latin impinging on the Celtic of France, etc. Nowadays we have a worldwide communications system which keeps together those languages which are together already and we can’t afford not to. My prediction is that English will not split off into separate languages. It shows no signs of doing so, and the last 100 years has seen a confluence rather than a centrifugal development in these languages. I’m far more interested in the fact that Spanish hasn’t split – it has had the diaspora far longer than English.

ME Do you think this could be because Spanish has a Royal Academy whereas English doesn’t?

RQ You could say Spanish has stuck together over 450 years of diaspora because it has the Real Academia and English will split up because after 350 years of diaspora there is no Academy. But Academies do not hold languages together. Nobody has ever measured the influence of Academies, but compared with the centripetal influence of government, the church and the media, neither the institutionalisational influence nor the stabilising influence of a Royal Academy is worth a fig in my view. It seems to me that the answer to your previous question is “Well, look at Spanish – if Spanish can stick together then so can English”. And because of the far more numerous roles that English has had imposed upon it the demands of keeping world-wide standards of English are much stronger that in the case of Spanish.

ME You made a binary cut between native English and non-native English; that of India and Nigeria on the one hand and Germany and the Soviet Union on the other.

RQ Yes. People in the British Council are used to making a distinction between ESL (English as a Second Language) and EFL (English as a Foreign Language). This is a distinction I have recently repudiated in my own work because I can no longer make the distinction with confidence. It seems to me that there’s an ethno-political bias in this very concept. It’s always been clear to me that every single ESL country that you can name is ex-Commonwealth. And, if there’s any EFL country on earth that is prototypical, then it’s Israel. There’s a lot of internal use of English but there’s no way I can tell an Israeli by his accent because each Israeli speaks English with the influence of his or her own background and Israeli Hebrew has not yet become so universal in Israel that it will become the native language and will start making an impact on others. But English is more important in Germany or Holland than in these other countries. If I were to stick my neck out I might say that I see English as playing a declining role in the ex-imperial countries. In India the Hindi belt is now such that they can afford to snap their fingers at the Tamil speaking minority who use English. It is true that Rajiv Gandhi was speaking English in a Tamil area on the day he was assassinated, but English plays a relatively minor role in India today and I believe it will eventually decline, as it will in Nigeria where it’s much more widespread than in India. The varieties of English that are worth taking a long and serious look at are the English of America and Britain, in that order.

ME Indira Gandhi once complained that she could not understand the English spoken by certain members of her own Parliament. Would you say they were ‘speaking the same language’ or that the communication breakdown indicates that there were two ‘Englishes’ operating in this instance, one based on “Standard English” and one local variety?

RQ I would say that the story of Indira and her MP was simply that she was well aware that her English was considerably better. We could have said precisely the same thing about Douglas Hurd going to an EC meeting in Brussels and complaining about one of the British Civil Servants not speaking French well enough. For Indira and her son, if English was a foreign language at all, it was a foreign language very well acquired. That’s a generation that’s going.

ME In another sense, it has been suggested that there are in fact two kinds of ‘standard English’ – one ‘complete version’ spoken by educated native speakers who use it as their first language, and a second, stripped-down and hence impoverished version, spoken by highly fluent speakers of English as a second language, and used as a world lingua franca in commerce, aviation, diplomacy, etc. Do you consider this a fair description, and if so, would you expect the two ‘versions’ to diverge, coalesce or maintain the same relation between them as at present?

RQ The short answer to this is no. But yes, in so much as there are several stripped-down versions. There is the Standard English of course, and the remarkable thing is that if you take a book by Patrick White or Antonia Byatt, you can read many pages before you decide that this must be a British, Australian or American writer. This Standard English is worldwide and has a continuity which most of us find reassuring. About thirteen years ago I floated the idea of a system of English called ‘Nuclear English’ in which we would have one stripped down version of English which was well designed and had a core vocab of about 2000 words in which you could say anything you wanted to say provided you didn’t want to be too poetic or too subtle. In this Nuclear English you could communicate everything using a grammar system which avoided all the modal auxiliaries which give our students so much difficulty – for example replacing ‘you may be right’ with ‘it is possible you are right’. It would give up the tag questions, using instead an ‘isn’t that so’ construction as in so many other languages. It would not deviate from standard English but by choosing with great care you could have a language that was much easier to learn, that was recognisable and usable all over the world and which would cost the poorer countries in this world which are pouring so much money into English language acquisition a great deal less in terms of national resources. I was also worried about the danger of the institutionalisation of Indian English and Nigerian English and felt that if that came about there would be a spiralling downwards because, without that native base, what is accepted in 1974 as ‘good English’ is passed on to the next generation only superficially – we can never teach all that we know ourselves. This was just a vague idea, but a couple of years after that with the aid of Robert Maxwell we floated something called ‘Seaspeak’. We had a reasonably effective system for Air navigation and the people who had the greatest difficulty learning this were the natives because they have to constrain themselves downwards rather than acquire new habits as the foreign learner does. The shipping companies were losing enormous amounts of money through accidents and additionally the level of education of the people involved in running ships is generally lower than in aviation. So a different cut down version was a definite necessity which Seaspeak was designed to fulfil.

ME How has English language teaching in the United Kingdom been affected by the development of an increasingly multiracial society? One would imagine that there might be a growing call for familiarity with EFL/ESL techniques within the British educational system.

RQ I wouldn’t want to give this too much emphasis. It is a very small sector of the English school population, but it may be eight to ten per cent or higher in some inner cities. Although local authorities have differed in the enthusiasm and professionalism with which they have taken this up, most London or Bradford schools, to give two examples, do have especially trained teachers who are aware that some of their children come from non-English speaking backgrounds . It particularly affects people from Moslem homes where the mothers have very little opportunity to socialise and therefore the language that they hand on to their children is Urdu or something similar. But I still hope that this is a passing phase and that increasingly the mothers will become the girls who went to schools here. It has been worrying and it continues to be so, and it’s an issue that’s become politicised in certain areas where manipulation of ‘consciousness raising’ is prevalent in immigrant communities.

ME You have in the past used the term ‘liberation linguistics’, presumably by analogy to ‘liberation theology’. Do you consider that language policies are inevitably subject to political and ideological considerations? And did you coin the phrase?

RQ Yes, in fact I did coin the phrase. Just as the liberation theologians wanted to dance a naughty tango with the Church of Rome and have the best of both worlds by playing a double game, I know that some of the people I have dubbed ‘liberation linguists’ have, to quote Pope, only a very little learning and that they have used it very dangerously. Language policies are inevitably subject to political and ideological considerations. It is unfortunate that the latter aspects of this have become (in my view) overly dominant, to the detriment of education. The way in which my wife and I have tried to put it in our book “English in Use” is that it is the job of education to make people into fit citizens and that means the wider the horizon the better the citizenship. Anything which raises boundaries between party and party or language community and language community is something that education is fundamentally concerned with destroying.

ME In a country like Argentina, where a great many people are actively involved in the teaching and learning of English as a Foreign language, do you consider that exposure to a single ‘standard’ (perhaps Standard British or Standard American) or to different ‘varieties’ (e.g. UK regional, would be the best strategy?

RQ In Argentina it is interesting how relatively little overt influence American English seems to be having, although some of the personnel in hotels are perhaps an exception. Despite being a long way from the UK or any UK based standard, the resistance to American English seems to still be quite strong. This afternoon I was at a seminar of 22 people where only one person spoke as if she had studied in the United States. My answer to this is that you can only really teach the English you know and fortunately the differences between British and American English, the two main standards, are, accent aside, sufficiently small that you don’t have to worry about it too much. In Argentina there is obviously a British standard and an American standard.

ME There is currently a debate about the relative merits of professionally trained local EFL teachers and ‘imported’ native speaker teachers. Do you have any strong feelings with regard to one being more suitable than the other in different teaching situations?

RQ I was talking about this at this afternoon’s seminar. I was really rather horrified to find that (in Argentina), unlike in Santiago and Valparaiso, there is very little native-English speaker input at university or teacher training level. The British system (although we are awful at learning languages) and the German Lektor system give this possibility. However if I had to choose between the two I would prefer the non-native teacher. The teacher with the same language background as the pupils doesn’t speak English as well but he has a much better grasp of pupil’s problems than the native-English teacher does and therefore can grade the learning. Native-speaker teachers have to be much more disciplined and much better trained than the non-native speaker in order to teach English as a foreign language . Ideally a group of half a dozen Argentinian non-native teachers ought to have a native Lektor that can take conversation classes, and so on.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Professor Sir Randolph Quirk was born in 1920 in the Isle of Man. He has been a lecturer in English at University College, London, Reader and Professor of English Language at Durham University, Quain Professor of English Language and Literature at UCL, Vice-Chancellor of the University of London and President of the British Academy. In 1959 he founded the Survey of English Usage, continuing as its Director until 1981. His publications include ‘An Old English Grammar’ (1955), ‘The Use of English’ (1962/68), ‘A Grammar of Contemporary English’ (1972), ‘The Linguist and the English Language’ (1974), ‘A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language’ (1985), ‘Words at Work: Lectures on Textual Structure’ (1986), ‘English in Use’ (1990) and ‘A Student’s Grammar of the English Language’ (1990). He maintains an active interest in Old English, Old Icelandic texts, the language of Dickens and Shakespeare, the teaching of English, English as an International Language and research and publications on English grammar. He is married to Gabriele Stein, Professor of Linguistics at the University of Heidelburg.

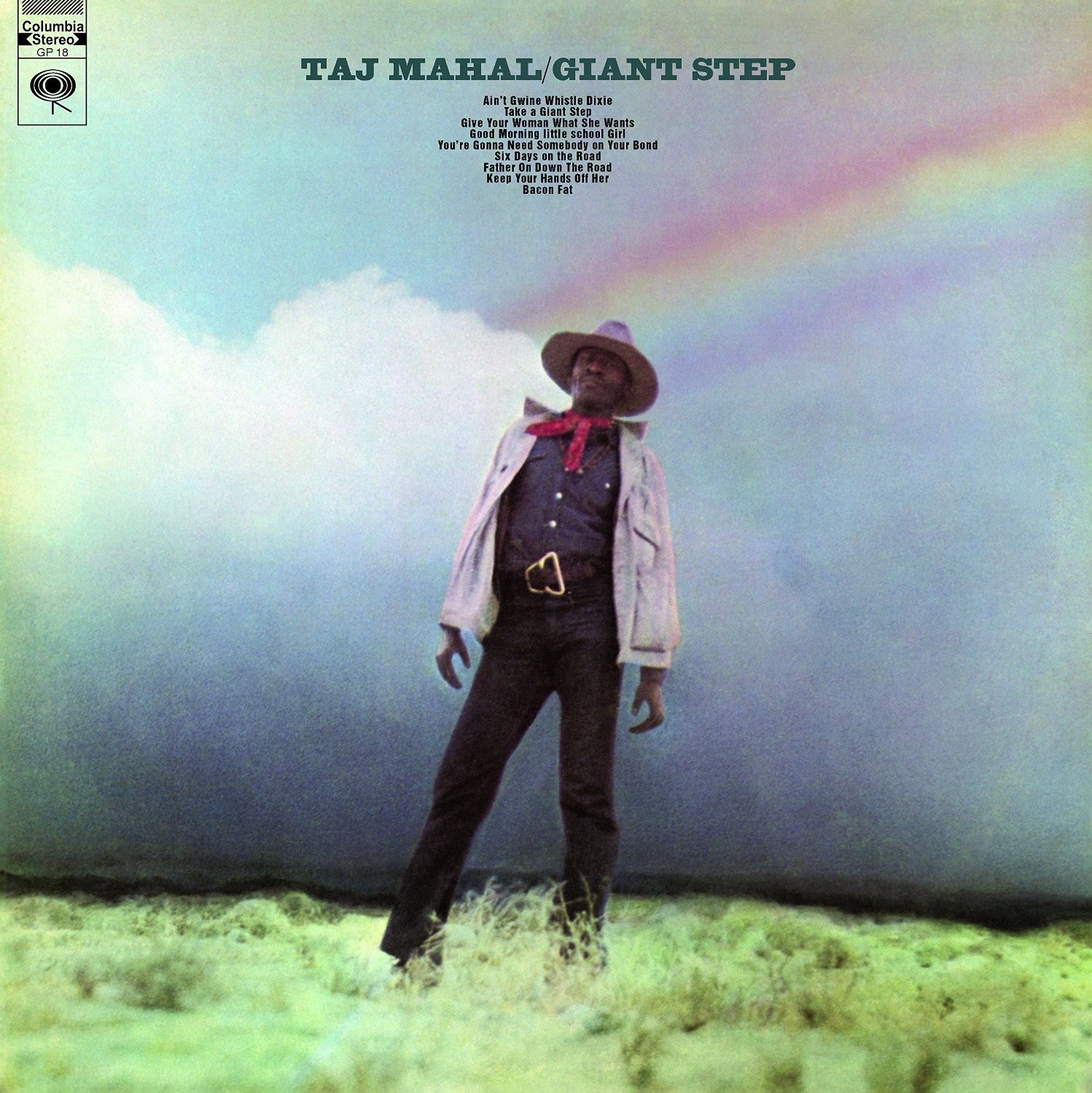

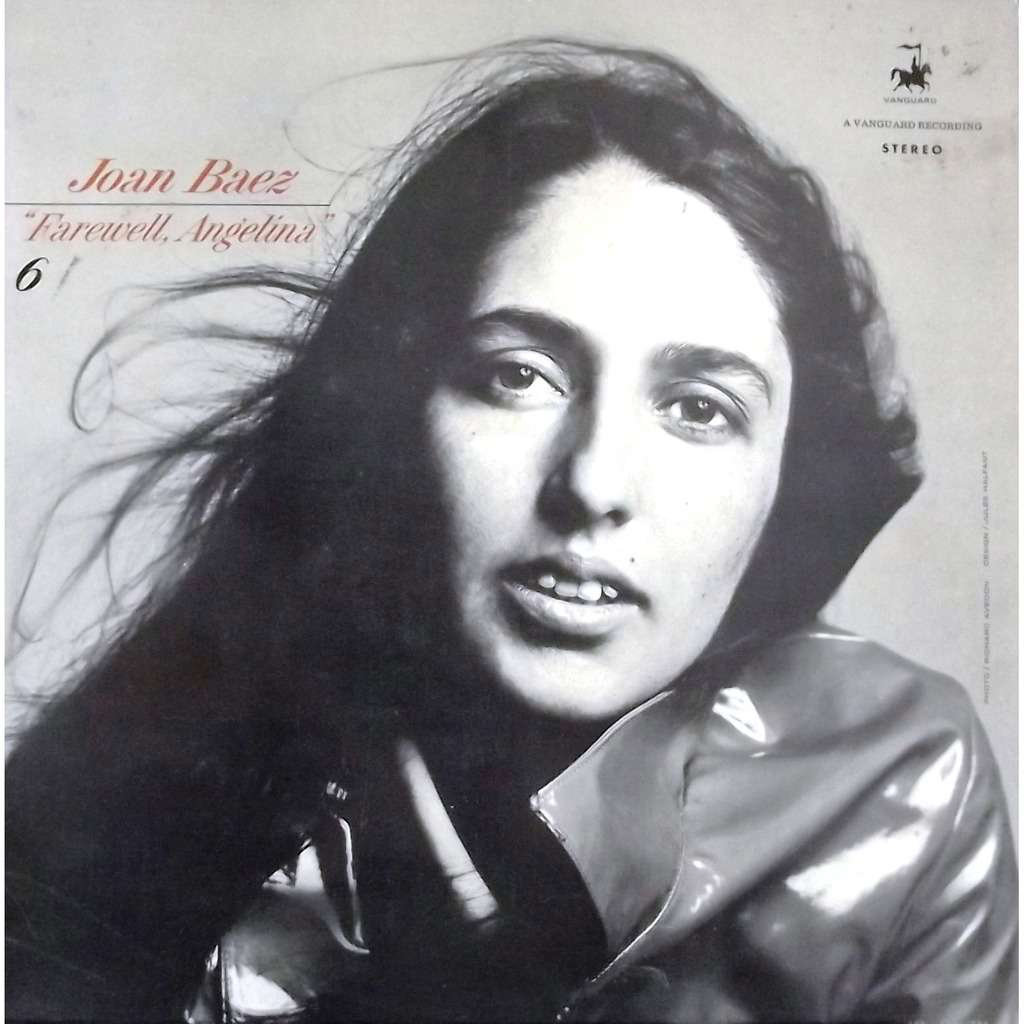

I first heard this album in 1965, when I was just 17 and living on the beach in Málaga. It was an exciting time for me, a time of discovery; sex, drugs and … well not exactly rock and roll, not just yet, but certainly folk and blues. And a bit of flamenco. It was in every sense of the word a formative time for me.

I first heard this album in 1965, when I was just 17 and living on the beach in Málaga. It was an exciting time for me, a time of discovery; sex, drugs and … well not exactly rock and roll, not just yet, but certainly folk and blues. And a bit of flamenco. It was in every sense of the word a formative time for me.